Andy White: Beatles Session Drummer

11th September 1962 : EMI Studios, Abbey Road

Andy White was about to become The Fourth Beatle. A week after their first session at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios, The Beatles were once again walking through its doors. That, however, was only a fantasy at this stage. They hadn’t even managed to make their first record yet. Today would have to be the day they accomplished this, because there would be no more studio time.

In his various books and interviews, George Martin has often confused the 4th September session with the 11th September session. That was his first meeting with Ringo, confirming that the 4th September session was not expected to produce a record.

As Martin once stated: “On 11th September 1962, we finally got together to make their first record. The boys meantime had brought along a guy, and they said ‘we’re going to get Ringo to play with us’. I said ‘we just spent good money and booked the best drummer in London. I’m not having your bloke in. I’ll find out about him later. Poor Ringo was mortified and I felt sorry for him, so I gave him the maracas”. On Anthology Martin said: “when Ringo came to the session for the first time, nobody told me he was coming. I’d already booked Andy White and told Brian Epstein this.”

George Martin was so exasperated with getting The Beatles’ first single recorded that he didn’t attend the second recording session. He left producer Ron Richards to oversee it.

Ringo was Shocked!

Following the 4th September session, George Martin decided that Ringo’s drumming was not what he was looking for. Therefore, he booked Andy White to make the record. As Ringo later observed: “I went down to play. He didn’t like me either, so he called a drummer named Andy White, a professional session man, to play”. That must have been devastating for Ringo. Was his career with The Beatles ending before it had begun? Ringo, unsurprisingly, was crestfallen. “I was devastated he (George Martin) had his doubts about me. I came down ready to roll and heard, ‘We’ve got a professional drummer’. He has apologised several times since, had old George, but it was devastating – I hated the bugger for years” (Anthology).

Ringo also told Beatles biographer Hunter Davies: “I found this other drummer sitting in my place. It was terrible. I’d been asked to join the Beatles. Now it looked as if I was only good enough to do ballrooms with them, but not for records. I thought; that was the end. They’re doing a Pete Best on me. I was shattered. What a drag. How phoney the whole record business was; I thought. Just what I’d heard about. If I was going to be no use for records, I might as well leave. What could the others say, or me? We just did what we were told.”

No Room for Sentiment

Much like the June session, John, Paul and George didn’t mention the personnel change to their drummer; in June, it was Pete – in September, it was Ringo. You have to wonder why they failed to tell him earlier that week that he was not going to be playing on the next recording session. What kind of friends were they, not giving him advance notice that he was being replaced by a session drummer? It all came down to business. This was their last chance, and there was no room for sentiment.

Geoff Emerick was sitting in the control room when Ringo walked in. “Dejectedly, Ringo sank into a chair beside Ron, and the session got underway.”

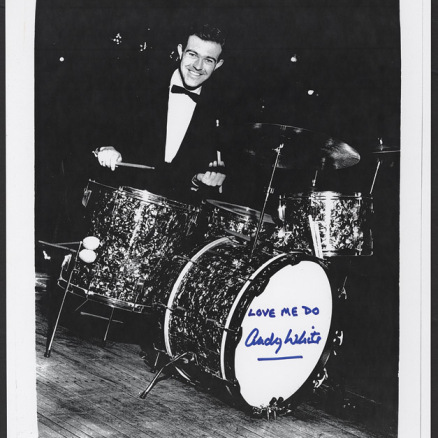

The Session Drummer

“On ‘Love Me Do’, they were only recorded on mono at first,” said producer Steve Levine. “They moved to mono on twin-track so they could record the backing tracks. Then they overdub the vocals on the other track”. That is why it was crucial to have the session drummer at the beginning. The whole rhythm track would be mixed and recorded on one track. It had to be right. You could not re-do the drums or guitars. Drummers like Andy White were worth their weight in gold, and always in demand.

In my interview with Andy White for The Fab one Hundred and Four, he told me that he was contacted by EMI for the job. “I received a call a few days before the session from the ‘fixer’ at EMI,” said White. “Every record company had a guy, who would contact the session musicians and book them for a particular gig. I received my call from EMI. It was only when I walked in on the morning of 11th September I realised it was Ron Richards producing the session”.

White remembered Ringo walking in on 11th September. “Ringo walked in with the others, and was obviously shocked to see me setting up my drums,” he said. “It was clear nobody had told him he was not going to be playing, and so we said ‘Hello’. He must have thought I was going to replace him, but I was ten years older than him. I’d have needed a wig after a year with them!”

Working with John and Paul

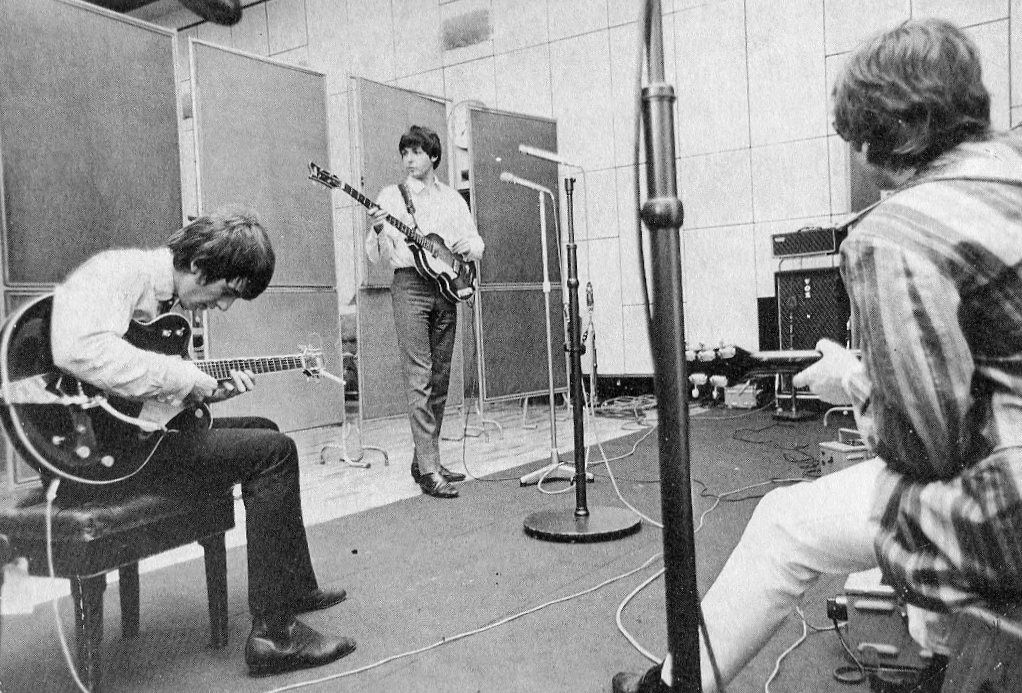

White had no prior knowledge of the group or the songs they would be recording. That was the usual practice for session drummers. “As with any session, I had no knowing what I was going to be doing that day. We sat down and discussed the songs. Most of the time I was talking with John and Paul, as they were the songwriters. Of course, they had no written music, but that was fine. They knew what they wanted to do, so we set to work. I was really impressed with them, and it was a nice change to be working on original songs. We worked through the routines and started rehearsing. Most of what I was trying to do was work with Paul and match what he was doing with the bass guitar”.

Recording Session: 4.45pm-6.30pm

Andy White’s presence in the studio demonstrated why George Martin’s decision was such an important one. The studio was booked between 4.45pm and 6.30pm, which didn’t leave them much time. In less than two hours, they managed to commit to tape excellent versions of “Love Me Do” and “P.S. I Love You”, and also a couple of takes of “Please Please Me”. The difference in studio time spent this day compared with the previous session was incredible. The Beatles had also now recorded three versions of “Love Me Do”, each distinctive, and each with a different drummer.

P.S. You Love Me?

With Andy White on the kit, The Beatles first recorded “P.S. I Love You” and then “Please Please Me” to see which of the two would best serve as the B-side. Emerick remembers them playing “P.S. I Love You”. After a few run-throughs, and ten takes, he was amazed at how “White seemed to get the hang of it. I was amazed at how quickly he did so, and how well he fit in with three unfamiliar musicians. The mark of a great session player.”

Ron Richards suggested to Ringo that he could go downstairs and join in with them, though only to play maracas. Emerick could “sense that he (Richards) was getting increasingly uncomfortable at having the sulking drummer sitting beside him. This must have struck him as a good way of getting Ringo out of the control room.”.

Love Me Do

After successfully recording “P.S. I Love You” and a run-through of “Please Please Me”, they got down to recording a third version of “Love Me Do”. Ron Richards called them back to their places quickly, aware of the passing time. “Now we need get back to work,” he said. “George wants you to have another go at ‘Love Me Do’”. Geoff Emerick remembers Ringo looking expectantly at Richards, “but Ron shot him down again. ‘I’d like you to play the tambourine on this, Ringo; we’ll stick with Andy on the drums.’”

Again, it took White only a short time to familiarize himself with the song. “His timekeeping was definitely steadier than Ringo’s had been the previous week,” recalled Emerick. “The other three were playing a lot better, too, and Paul sang the lead vocal with much greater confidence”. It was obvious to Richards and Emerick that the Beatles had done a lot of rehearsing during the week.”.

Norman Smith affirms the choice of Andy White, a drummer he knew well. “He started playing exactly as I thought the song should have been played, and how it should be done. Andy White was great, and so we created the master.”

Please Please Us

George Martin turned up towards the end to the session to see the group, and what progress had been made. Ron Richards could happily inform him that, in just under two hours, they had recorded both the A-side and B-side. “Please Please Me” was then run through and recorded with the modifications Martin had suggested the previous week. However, it still wasn’t the finished article. Even so, it was vastly improved.

Again, White played the drums, with no contribution from Ringo. He gave the song an exciting rhythm, and his musical rapport with the other three Beatles was incredible. In less than two hours, they had taught him – and recorded! – three original songs. That is the difference a session drummer can make. With the White version of the song now completed, Ringo was able to use it to create a similar drum pattern when the group re-recorded the song on 26th November 1962.

Comparing Andy White and Ringo

How do the two versions compare? “It’s a strange one,” said Alex Cain, “because on this occasion Ringo displays more solidity than the seasoned-pro. Ringo plays solid ‘8 in the bar’ ride cymbal throughout. Andy offers a softer approach, playfully landing on his hi-hats around the snare beats, producing a stop-start feel. White’s fills are somewhat hurried where he sounds as if he’s thrown his drums down the stairs! Personally, I much prefer Ringo’s performances, both in the studio and live. It makes for a more energetic and youthful sound overall”. Did Ringo’s performance on 26th November convince George Martin to stick with Ringo, and not use a session drummer again?

However, for the recording of “Love Me Do”, everyone was happy; except for poor Ringo.

Love Me Do or Love Me Don’t? Comparing the Ringo and Andy White Versions

In his book I Want To Tell You, Anthony Robustelli examined the two September versions of “Love Me Do”. “The second version of ‘Love Me Do’ (Andy White’s version) is five faster and therefore, rocks a little harder. The recording is far superior sonically to the other version with the kick and snare punchy in the mix. Furthermore, Andy White’s kick drum pattern is much busier, and though it seems to lock in with the bass better. It’s difficult to compare the kick’s feel because of the drastic sonic differences. On the original September 4th version with Ringo, the kick is barely audible. White’s more swinging kick drum definitely propels the song forward more successfully. The sonic punch and clarity undeniably helped, as did the addition of Ringo’s tambourine and an additional five BPM.”.

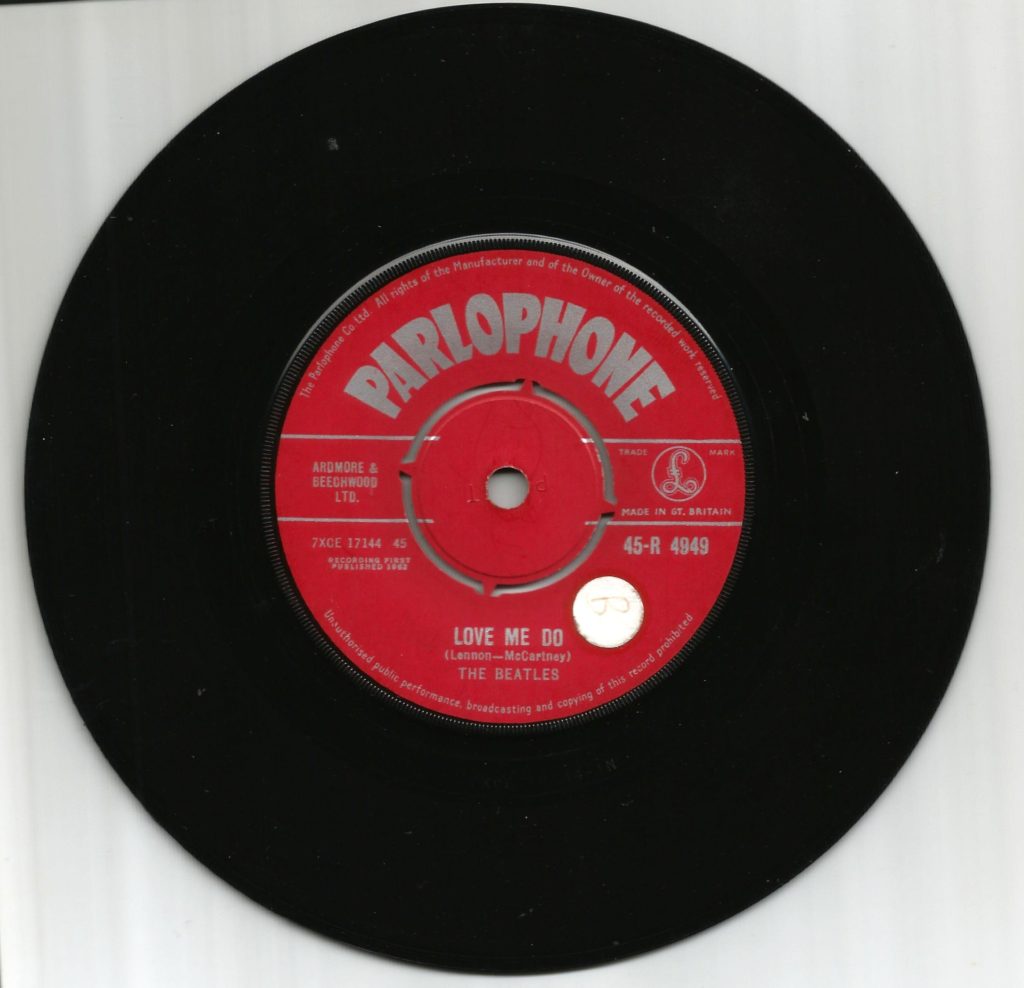

“Ringo Didn’t Drum on the First Single”

Paul was convinced that Ringo didn’t play drums on the group’s first Parlophone single, “Love Me Do” – and Ringo agreed. Yet history has shown that he was indeed on the UK single release. Considering that Andy White was hired to drum on the recording: Was Ringo’s version mistakenly released on the UK single? After all, the White version of “Love Me Do” appeared on The Beatles’ debut studio album Please Please Me. The UK EP release The Beatles’ Hits, and also on their U.S. single release.

Is there any evidence to support this?

If the Ringo version wasn’t considered good enough after 4th September, why release that first version? Neither George Martin nor Ron Richards were sure if it was selected intentionally or not.

The releases of “Love Me Do” issued after The Beatles’ Hits on 21st September 1963 contained Andy White’s version. Why? The original master recording of Ringo’s version of “Love Me Do” destroyed or recorded over, possibly as early as 1962. EMI only had Andy White’s 11th September recording to use. It was the only remaining – and arguably the superior – version. When “Love Me Do” was released in the U.S. in April 1964, it was Andy White’s version that was used.

The final piece of evidence is one of omission. With the group’s popularity in 1963, why did they not ask Ringo to re-record “Love Me Do” for the album? Instead, they used Andy White’s version? The conclusion is that Ringo’ version was most likely released by accident. Nothing else really makes sense.

No More Session Drummers

Although George Martin wasn’t impressed with Ringo’s drumming, he grew to appreciate his style. They soon became good friends. The producer would replace him only one more time by a session drummer – Bobby Graham. “Ringo always got, , a unique sound out of his drums, a sound as distinctive as his voice,” Martin said. “Ringo gets a looser deeper sound out of his drums that is unique. This detailed attention to the tone of his drums is one of the reasons for Ringo’s brilliance. Although Ringo does not keep time with a metronome accuracy, he has an unrivalled feel for a song. If his timing fluctuates, it invariably does so in the right place at the right time. He keeps the right atmosphere going on the track and giving it a rock-solid foundation. This held true for every single Beatles number Richie played Ringo also was a great tom-tom player”.

Martin added: “Ringo has a tremendous feel for a song, and he always helped us hit the right tempo the first time. He was rock solid. This made the recording of all the Beatles songs so much easier.”

An excerpt from “Finding the Fourth Beatle” by David Bedford and Garry Popper

David Bedford

Add comment